Historic Fort Washington on the Potomac

By James Dudley Morgan, M.D. (Read before

the Society, January 12, 1903.)

The strategic

advantage of that promontory on the Potomac, which is now called

Fort Washington, seems to have been known to the Indians, long

before the coming of the white man into this region. That these

aborigines appreciated the natural advantages for defense and

offense offered by this bluff at the junction of the Potomac

River and Piscataway Creek, and that their judgment and choice

of the situation were both sound and unassailable is attested by

the continued occupancy of this mound for hostile defense by the

first colonial settlers under Governor Calvert; by its choice as

a point for a fortification by Generals Washington and Knox; by

its improvement and enlargement under Presidents Madison and

Monroe, and by its reaching at our present day the distinction

of flying the garrison flag.

First Period

The colonists

from England, in the Ark and the Dove, penetrated as far up the

Potomac River as what is now called Heron and Black stone

Islands, before disembarking. Leaving most of his party here.

Governor Leonard Calvert, with a few chosen men of the party,

set out in two pinnaces to further explore the river. They made

several landings, one about four leagues up at a point near the

present Colonial Beach, but here the natives on their approach

became alarmed and fled into the interior. Their next stop was

after sailing about nine leagues, which brought them to what is

now called Marlborough Point.1 Here

the Indian chief, Archihu, met them in a friendly manner and

said, "You are welcome; we will use one table; my people shall

hunt for my brother." Continuing their voyage of discovery, they

came to what was then and is yet called Piscataway Creek, and

here they found the surrounding heights covered with Indians, to

the number of about five hundred, in hostile array. After long

and patient gesticulations and demonstrations, the colonists

convinced the natives that their mission was peaceable, and a

conference with their chief then took place. It was here that

the English found Henry Fleet, who had been captured and held as

a prisoner, and through his acting as interpreter much good

feeling was shown.

Shortly after the arrival of Governor

Calvert and his party at Piscataway Creek the Indian chief fell

ill, and forty conjurers or medicine men in vain tried every

remedy within their power; when one of Governor Calvert's party,

a Father White, by permission of the chief administered some

medicine to him and caused him to be freely bled; the treatment

was successful, the invalid began to improve, and was soon

restored to perfect health.2 The

chieftain, though, would not bid Calvert and his men either go

or stay, but told him "he might use his own discretion.

''Governor Calvert, not over pleased with the dubiousness of his

welcome, thought prudence was the better policy, and deeming it

unwise to settle so far up (150 miles) the Potomac, after having

by various presents persuaded the chief of the Piscataways to

allow Henry

Fort Washington

Mt. Vernon

Fleet to

accompany them, returned for his copatriots, who were awaiting

him at Blackistone's Island, and entering the river now called

the St. Mary's, and about ten miles from its junction with the

Potomac, purchased of the Indians part of their village, where

he commenced his settlement to which was given the name (March

27, 1634) of St. Mary's. This purchase of land and treaty with

the Indians was much facilitated by a happy occurrence, at least

for the colonists, which took place at this time. The

Susquehannock Indians, who lived about the head of the bay, were

in the practice of making incursions on their neighbors, the

Yoamacoes, in the vicinity of St. Mary's city, partly for

dominion and partly for booty, and of the booty women were

mostly desired. The Yoamacoes were at this very time fearing a

visitation of the Susquehannocks, and had already gotten to a

point of safety many of their wives and sweethearts, so that

striking a bargain for the purchase of the land was rendered

very easy for the colonists.

It was but

eleven years after (1645) the establishment of St. Mary's city

(1634) that among the many acts and regulations for the defense

of the province, we read of one for the establishment of a

garrison at the mouth of the Piscataway Creek, and authorizing

"Thomas Watson of St. George's Hundred to assemble all the

freemen of that hundred for the purpose of assessing upon that

hundred only the charge of a soldier, who had been sent by that

hundred to serve in the garrison at Piscataway."3

In Ridpath's "History of the United States," page 219, we read

as follows: "On the present site of Fort Washington, which is

nearly opposite Mount Vernon, the Indian village of Piscataway

stood. Here Gov. Leonard Calvert moored his pinnace and held a

conference with the chief of the Piscataways." "This Indian

village," says Willson, in his history, "was fifteen miles south

from Washington on the east side of the Potomac at the mouth of

the Piscataway Creek, opposite Mount Vernon and near the site of

the present Fort Washington." An Indian settlement appears on

John Smith's map of Virginia, opposite Mount Vernon, at the

mouth of the Piscataway Creek.

Second Period

It is always

a subject for congratulation that any enterprise in connection

with the interests of our young republic was either instigated

by or had the endorsement of General Washington. He evidently

weighed well and considered and overlooked the whole field of

facts before promoting or sanctioning an innovation. That he

might gain a more thorough knowledge of the topography of the

country surrounding our Federal City, and the course and

tributaries of the Potomac he, in 1785, accompanied by several

friends, among whom was Governor Johnson of Maryland, made a

tour of investigation, in a canoe, of the upper Potomac, long

before the removal of the seat of government to Washington. So

it was before recommending to General Knox that promontory on

the Potomac for a fort (1794)4 that

he had overlooked, examined and sojourned in the immediate

neighbor-hood and consequently was thoroughly familiar with the

locality and knew of its many advantages. It was often his

custom in going either to Bladensburg, Upper Marlborough or to

Annapolis to ferry the Potomac from Mount Vernon to Warburton,

and thus continue his journey. He has often, when tired or

belated, or for social intercourse, stopped and spent some time

with George or Thomas Digges at Warburton what is now Fort

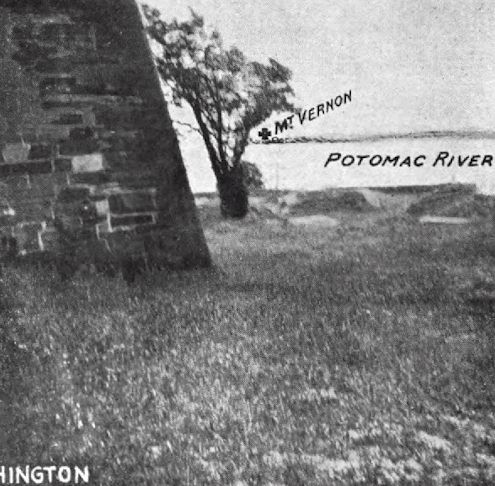

Washington. The writer has heard Dr. Joseph M. Toner, in

speaking of the beautiful and unobstructed view from Mount

Vernon to Warburton5 (now Fort

Washington), narrate the story taken from Washington Irving's

"Life of General Washington," of how General Washington stood on

that knoll, a little to the front of his home, and through that

forest vista signaled by flag to Warburton. Then their little

boats with liveried men would pull out from the shores of the

Potomac, to bear the invited one to Mount Vernon or Warburton,

or to strike a trade perchance of tobacco, corn, or wheat, for

cattle or sheep, or what not.

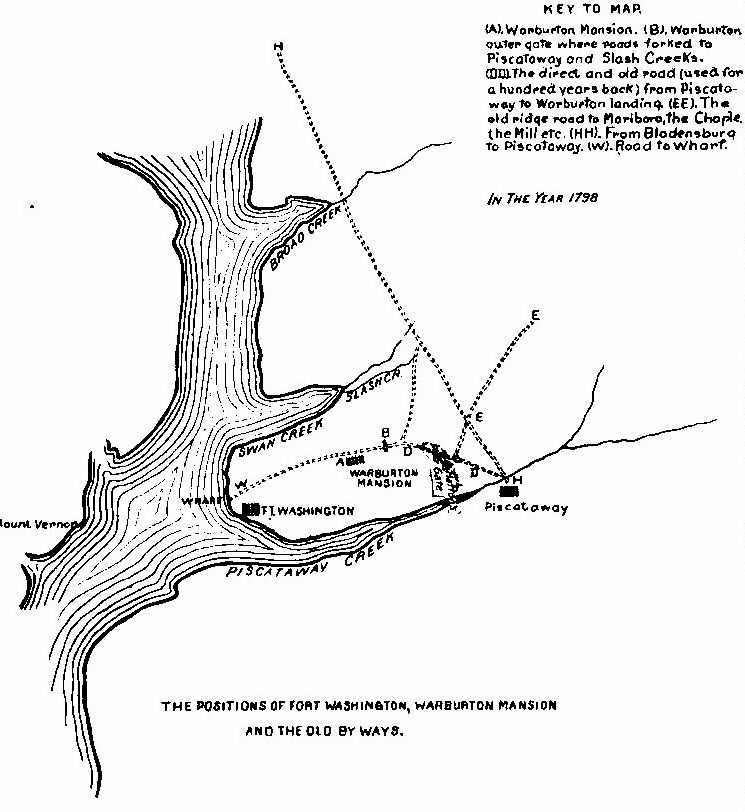

From Old Maps of the Potomac

River and its Environments, by Dr. James D. Morgan

Exhibit 1

Warburton April 7, 1775.

Dear Sir

My Father & Mr. Hawkins will take four, hundred Bushel

of your Salt, & I will copy a few Advertisements to be

put up in this Neighborhood, your Vessel may come along

side of our Warf, which I apprehend would be more

Convenient for the people that may want to purchase.

"At Fort Washington, now Fort Warburton." "In August,

1814, the troops stationed at Fort Warburton, the only

defense of Alexandria, blew up the magazine, and

abandoned the fort." Pages 15 and 128, "Description of

the Territory of Columbia," Warden, Paris, 1816.

"In the same despondent hour, when General Winder

declared that Fort Warburton was not tenable. * * *

"Historical Sketch of Second War between United States

and Great Britain," by Chas. J. Ingersoll, p. 181, Phila.,

Lea and Blanchard, 1849.

The family Join in Complts to all at Mt. Vernon, with

Dear Sir

Your Most Ob Sert.

Geo Digges

(Addressed to) For Col. George Washington at Mount

Vernon. |

The Manor of

Warburton was patented in October 20, 1641. Bounded by

Piscataway Creek, Potomac River and part of Swan Creek by

natural boundary's, etc., makes it 1,200 acres more or less.

Short entry of the certificate is dated June 20, 1637.

Exhibit 2

(To

Thomas Digges about exchange of wheat, from Gen.

Washington.)

Genl. Washington presents his

compliments to Mr. Digges, and will, with pleasure,

exchange 20 bushels of the early White Wheat with him

when he gets it out of the straw; which is not the case

at present, nor can be until the latter end of next week

or beginning of the week following: which would be full

early for sowing that kind of Wheat. Indeed any time in

September, is in good season. The middle, better than

sooner in that month.

A good journey to Mr. Digges

Mount Vernon 31. Septr. 1799.

|

Thomas Digges of Warburton

Manor

From portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, in possession of Mrs. Ella

Morgan Speer

There was

evidently much social visiting between the Washingtons and the

families at Warburton and other neighboring country seats. In

addition to the hospitality extended during the hunting season,

Mr. Irving speaks of "water parties upon the Potomac in those

palmy days, when Mr. Digges would receive his guests in a barge

rowed by six Negroes arrayed in the uniform, whose

distinguishing features were checked shirts and black velvet

caps. As Mr. Irving's 'palmy days' were before the Revolution,

the Mr. Digges referred to was evidently Mr. George A. Digges,

who lived at Warburton, until his death in 1792. At this time,

Warburton passed into the hands of a bachelor brother, Thomas.

As was customary with the sons of the Maryland and the Virginia

planters, Thomas Digges had spent his youth in London, where he

was known in his circle of friends as the handsome American.

Although young Digges lived the life of a youth of fashion among

the 'Macaroni' of his day, when his services were needed by his

country, he proved him-self to be a man of resolute character,

and ardently patriotic. The Continental Congress required a

secret and confidential agent near the Court of St. James, and

Thomas Digges was, through the influence of Washington, selected

for this hazardous and important mission.''6

Exhibit 3

(Addressed to)

His Excellency General Washington at Mount Vernon

Virginia.

(Endorsed by Washington)

From Thomas Digges Esq.

10th April 1798.

Mr. Digges presents His respectful compliments and best

wishes to General Washington and sends this in a small

box of seeds, which accompanies a few Potatoes of a

remarkably approved kind & productive Growth, which Mr.

Rhd. Edmonds Seedsman No. 96 Grace Church Street London

handsomely offered to and pressd Mr. D to present in His

name to General Washington.

Mr. Chs. Pye, who has also purchased some seeds of Mr.

Edmonds with me, has promised to take care of them, He

being one of the passengers by the Mount Vernon Capt.

Johnson bound to Alexandria.

The Potatoes and the Garden Seeds are obliged to be put

in separate parcels for fear of the yielding damp of the

former hurtling [sic] the seeds.

Mr. Rhd. Edmond's

No. 96 Grace Church Street

London 10th Apl. 1798.

Mr. Digges has taken the liberty to send in the Box of

Seeds a few late News Papers. |

Exhibit 47

Annapolis

Jany. 5, 1787. Dear Sir

Mr. Gillis's Polk (who is now here) & lives at Salisbury

in Somerset County will Immediately upon his return home

have the plank sawed agreeable to your direction & also

will forward it by the first Opportunity. Our Senate

have rejected the Money Bill & this day we expect a

Message from them given their reasons. We have done

little or no Public Business nor. doe I believe we shall

as there seems to be a Party for breaking up at all

events next Week

with Compts. to Mrs. Washington & family am

Dear Sir with great Respect

Yr. Most Obt. Sert.

Geo. Digges

N. B.

I did not get yr. letter till after the Post left Town &

Mr. Powell the bearer of this has promised to forward it

- To Genl. Washington.) |

Third Period

From the

period of about 1795, when negotiations were entered into with

Mr. George Digges for the purchase of part of Warburton at the

mouth of the Piscataway Creek, on the Potomac River, for a fort,

and the further expense to the government of small sums of money

for entrenchments at that point, there was very little done,

until President Madison, aroused by the imminent danger of war

with Great Britain, directed that Major Pierre Charles L 'Enfant

proceed to Fort Warburton and report to the Secretary of War the

condition of that defense. Major L'Enfant, in a written report

(May 28, 1813), told of the dilapidated condition of the fort

and the armament, and urged a suitable appropriation for putting

the fort in proper condition for the defense of the Potomac and

the Federal City. He spoke of the necessity of an additional

number of heavy guns at Fort Warburton and an additional fort in

the neighborhood, and concludes thus: "That the whole original

design was bad, and it is therefore impossible to make a perfect

work of it by any alterations." To prove that L 'Enfant believed

firmly in adequate sea and coast defenses, and that the best way

to prevent war was to be prepared, the following very

interesting and instructive extract from one of his letters to

General Washington dated September 11, 1789, is quoted:

"And now that I am addressing your

Excellency I will avail myself of the occasion to call your

attention an object at least equal importance to the dignity of

the Nation, and which her quiet and prosperity is intimately

connected. I mean the protection of the seacoast of the United

States. This has hitherto been left to the Individual States and

has been so totally neglected as to endanger the peace of the

Union, for it is certain that an insult offered on this (and

there is nothing to prevent it) however immaterially it may be

in its local effect, would degrade the nation and do more injury

to its political interests than a much greater depredation on

her Inland frontier. From these considerations I should argue

the necessity of the different Ways and seaports being fortified

at the expense of the union, in order that one general and

uniform system may prevail throughout, that being as necessary

as a uniformity in the discipline of the Troupes to whom they

are to be entrusted.

"I flatter myself your Excellency

will excuse the freedom with which I impart to you my ideas on

this subject, indeed my Confidence in this Business arises in a

great measure from a persuasion that the subject has already

engaged your attention, having had the honor to belong to the

corps of engineers acting under your orders during the late war,

and being the only officer of that corps remaining on the

Continent." ***

Gen. Wilkinson in Williams' "Invasion

of Washington" at page 285 says:

"Fort Washington was a mere water

battery of twelve or fifteen guns bearing upon the channel in

the ascent of the river, but useless the moment a vessel had

passed. This work was seated at the foot of a steep acclivity,

from the summit of which the garrison could have been driven out

by musketry; but this height was protected by an octagonal

blockhouse, built of brick and of two stories altitude, which,

being calculated against musketry only, could be knocked down by

twelve-pounder."

This was its condition in July, 1813.

Still with all these facts before him

the Secretary of War, Armstrong, proceeded to argue the utter

improbability of a hostile force leaving its fleet and marching

forty miles inland; as to the Potomac, its rocks and shoals and

devious channels would prevent any stranger ascending it. "The

British," Armstrong concluded, "would never be so mad as to make

an attempt on Washington, and it is therefore totally

unnecessary to make any preparations for its defense.'' Not only

the Secretary of War, but also President Madison, did not see

the need of urgency, and only "a couple of hands" were ordered

down to the fort to execute the necessary repairs, so that the

ascent of the British in August, 1814, was checked by no

formidable display of men or of armament, and their approach to

Alexandria was easy and simple, having only one man killed in a

journey of eight to nine days or more up the Potomac, and this

Briton was shot lower down the Potomac raiding a chicken roost.

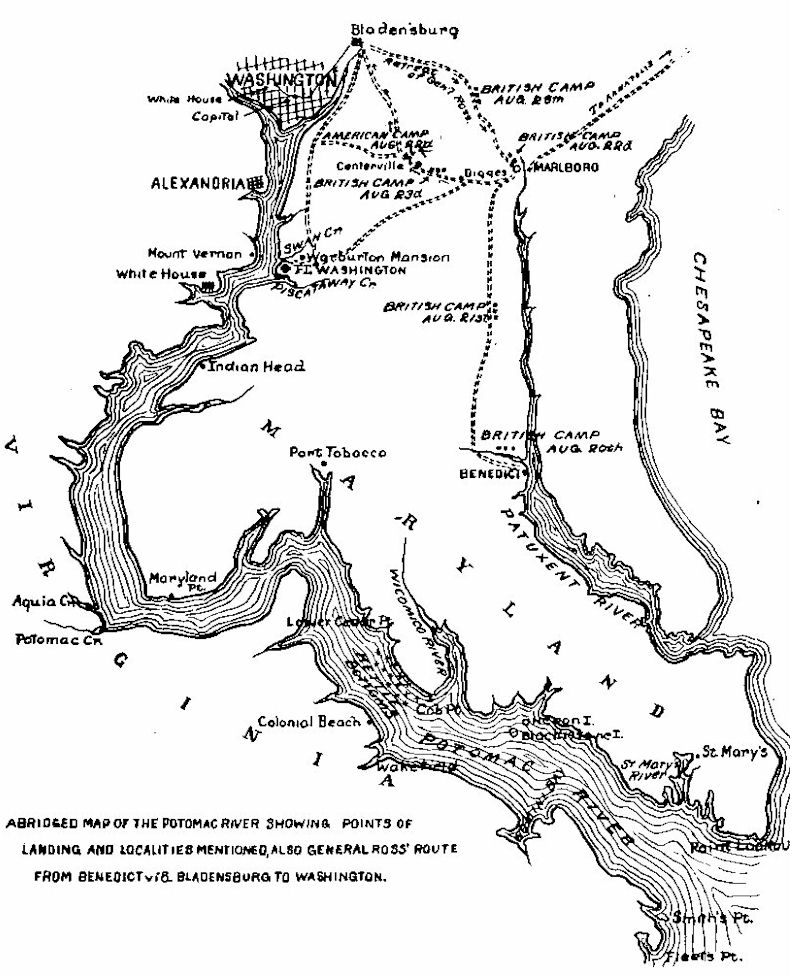

After the disgraceful capitulation of

Alexandria (and the burning of the public buildings of

Washington, by the other wing of the British army, which had

landed at Benedict on the Patuxant and come to Washington by way

of Marlborough and Bladensburg), Captain Gordon, the British

commander, weighed anchor and slowly proceeded down the Potomac.

At both the White House and Indian Head on the Potomac

(September 5, 1814) there was a considerable muster of men, who

fired upon the retreating vessels, towing their prizes taken at

Alexandria. Porter's battery at the White House did considerable

damage to the enemy, killing seven and wounding thirty-five men.

The winding course of the channel of the Potomac and the

numerous kettle bottoms8 formed by

beds of mud and oysters, made their navigation and speed very

slow, and on many occasions the vessels were grounded on one of

the frequent sandbars.

Only a few

days elapsed after the departure of the British, when Secretary

of State Monroe, who was then also Acting Secretary of War (Gen.

Armstrong having resigned in disgrace), ordered (September 8,

1814) Major L 'Enfant to proceed to Fort Washington and

reconstruct the fort. (Exhibit 5.)

An exhibit dated September 13, 1814,

ordering Major L 'Enfant to report to Col. Monroe, Acting

Secretary of War, is presented, also an exhibit dated Monday,

September 19, 1814, showing the amount of material and men sent

on that day to Major L 'Enfant at Fort Washington.

Exhibit 5

Washington Spt. 8, 1814

Major L 'Enfant

Sir

You will proceed to Fort Washington and examine the

state of that work, and report the same as early as

possible to

Yr obed sevt

Jas. Monroe |

Exhibit 6

To Major Longfoung

Topographical Engineer at or near Fort Washington

By Express.

Q. M. Genl. Office Washington City Sept. 13, 1814 7

O'Clock Evening

Major Longfaung

Sir

On receipt of this note you will repair immediately to

Washington City & Report yourself to Colo. Munroe Actg

Secy of War.

By Order F Marsteller

Q M Genl. |

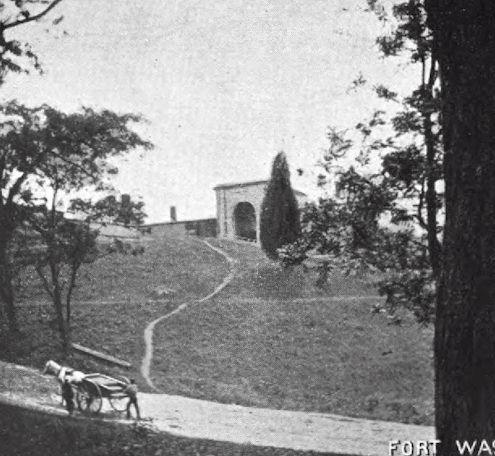

Warburton Mansion and the Old

By-Ways in 1798

Exhibit 7

On Monday 19th to be Sent to

Major L'Enfant at Fort Washington, 50 Men with 15 or 20

Wheelbarrows, Spade & pick axe & a Number of Good Axes.

Carts will be Wanted hereafter.

Timber will Also be Wanted for the Work And Some

Carpenters & Masons & About 20000 Bricks. Some rough

Stone & lime, of Which a note will be given by Major L

'Enfant.

Signed Jas. Monroe

Sept. 15th, 1814.

Major Marsteller

Materials Ordered from 500 to 1000 perch Stone

from 1 to 200000 Bricks

Timber 40 feet long- 14 Inches square- 30 pieces

Scantling 30 feet long - 6 by 9- 400 pieces

Plank 25 feet long - 3 or 4- about 5000 feet

1 Gin Complete with falls. |

Captain

Gordon, H. M. S. Seahorse, commanding the Potomac squadron, in

his report has this to say of that part of the journey in the

vicinity of Mount Vernon and Fort Washington:

''The following morning, August 27,

1814, to our great joy the wind became fair, and we made all

sail up the river, which now assumed a more pleasing aspect. At

five o'clock in the afternoon. Mount Vernon, the retreat of the

illustrious Washington, opened to our view, and showed us for

the first time, since we entered the Potomac, a gentleman's

residence.

Higher, up the river on the opposite

side Fort Washington appeared to our anxious eyes, and to our

great satisfaction, it was considered assailable. A little

before sunset the squadron anchored just out of the gunshot; the

bomb vessels at once took up their positions to cover the

frigates in the projected attack at daylight next morning and

began throwing shells. The garrison, to our great surprise,

retreated from the fort; and a short time afterwards. Fort

Washington was blown up, which left the capital of America and

the populous town of Alexandria open to the squadron, without a

loss of a man. It was too late to ascertain whether this

catastrophe was occasioned by one of our shells, or whether it

had been blown up by the garrison; but the opinion was in favor

of the latter. Still we are at a loss to account for such an

extraordinary step. The position was good, and its capture would

have cost us at least fifty men and more, had it been properly

defended; besides an unfavorable wind and many other chances

were in their favor, and we could have only destroyed it had we

succeeded in the attempt.

''At daylight the ships moored under

the battery and completed its destruction. The guns were spiked

by the enemy; we otherwise mutilated them, and destroyed the

carriages. Fort Washington was a most respectable defense; it

mounted two fifty-two pounders, two thirty-two pounders, eight

twenty-four pounders; in a martello tower two twelve-pounders,

with two loop-holes for musketry; and a battery in the rear

mounting two twelve and six six-pound field pieces.''

There can be no doubt that had Fort

Washington been properly garrisoned and the channel obstructed,

as General Winder requested (August 19, 1814), and suitable

batteries erected at the proper time on the river, the British

squadron would never have reached Alexandria. The officer

(Exhibit 8) who had run away with his command from Fort

Washington was tried by the court-martial and dismissed from the

service.

Exhibit 8

Adt. & Inspr. Genl's Office

Washington

Oct. 13, 1814

Sir:

You will attend as a Witness on the part of the prisoner

before the Genl. Court Martial sitting in this City for

the Trial of Cap. Saml. T. Dyon (?) on Thursday the 20th

inst.

I am Sir Yr. Obt Servt

Jn p. Bell (?) Maj. Genl,

Major L 'Enfant

Engineer Fort Washington |

A letter

dated Fort Washington, July 19, 1815, from L 'Enfant to Major

Marsteller, reads as follows:

Exhibit 9

Fort Washington

July 19, 1815 Sir

With pleasure I forward to you agreeable to application

an expression of my opinion of your character and

conduct during your attendance on Fort fort [sic]

Washington. I have Sir in all things that have come

under my notice found you correct & in conduct the

perfect gentleman.

P. Ch. L 'Enfant

to Major Marsteller, etc. |

After the

second war with Great Britain, Fort Washington was allowed, as

most of the fortifications throughout the United States, to go

to rack and ruin for want of proper care to its armament and

entrenchments, until in 1850 it was a mere military post, having

one or two companies of artillery, and later on only a

detachment of the ordnance corps.

Fourth Period

In all

periods of North American history, aboriginal, revolutionary and

successional, the ground where Fort Washington stands to-day has

taken a prominent part. The first order issued during the Civil

War for the protection of Washington to the naval forces was

dated January 5, 1861, signed Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the

Navy, and addressed to Col. John Harris, Commandant Marine

Corps, directing that a force of marines be sent to Fort

Washington, down the Potomac, for the protection of public

property. Forty men, commanded by Capt. A. S. Taylor, U. S.

Marine Corps, were sent in obedience to this order.9

Historic Fort Washington, which has

seen so many vicissitudes and taken part in so many wars,

invasions, sieges and insurrections of this country, had a

garrison flag raised to the top of a new steel flag pole, on

Wednesday, December 12, 1902, with military ceremony, the music

playing, troops drawn up in line with presented arms, and a

salute being fired from the guns of the fort. The new flag,

which is a large one, flies from the top of the pole fully two

hundred feet above the river. It is so situated on a high hill

that it can be seen for miles. Until this time only a small flag

had been used at Fort Washington on the flag pole within the old

stone fort. Under the authority of the War Department the large

garrison flag has now been raised, signifying Fort Washington is

the headquarters for the Potomac forts.

Discussion

Mr. M. I.

Weller said: While the able paper which has just been read by

Dr. Morgan deserves abundant praise, still I cannot allow this

occasion to pass without entering my protest against the

undeserved condemnation of the American army which was entrusted

with the defense of the National Capital and which was commanded

by that efficient soldier, General William H. Winder, who with

the hastily gathered forces made a determined defense against

Wellington's veterans fresh from the scenes of victories in the

Napoleonic wars under the leadership of General Ross who had

enjoyed a reputation second to none; I certainly believe at this

late day no historian who will have access to original sources

will repeat the slurs that were so prevalent shortly after the

disaster and which forced the Secretary of War, General

Armstrong, into retirement, the victim of public clamor; the

campaign lasted ten days with its culmination at Bladensburg,

where the forces engaged were nearly equal in number; the battle

was well contested, especially by the District of Columbia

contingent, numbering about 1,100 men, under the command of

General Walter Smith, and the sailors of Commander Barney's

flotilla, who served their guns with admirable precision until

their ammunition was exhausted ; the statement that the army was

panic-stricken so often mentioned is not based on facts, there

was no rout, but the retreat was effected in an orderly manner,

although some of the guns had to be abandoned; it is said that

when the order was given to retreat, the District contingent was

reluctant to leave the field and some even shed tears that they

should be compelled to retire; of course the defeat left the

road to Washington open, and the enemy entered the city, on

their mission of destruction, reaching Capitol Hill about eight

o 'clock P. M.; the main cause of the British victory was the

use of Congreve rockets, missiles of war totally unknown on this

side of the Atlantic and which had spread consternation in the

ranks of the French veterans at the battle of Leipsic, a year

previous; and which had the tendency to demoralize any troops

unacquainted with this naval implement of war; the British

forces fled precipitately from the city the following night,

after indulging in acts of vandalism disgraceful to England and

subsequently condemned by the civilized world; the British

casualties were over 1,100 in number, more than one fourth of

their total army, and in their retreat they abandoned their

wounded to the mercy of their American foe, who attended them

with such generosity" that it enlisted the grateful

acknowledgments of General Ross and Admiral Cockburn; this at

least is one of the bright redeeming features of this short

campaign and in vivid contrast to the unjustifiable deeds

perpetrated by their enemies; as a grandson of one of the

British invaders (my maternal grandfather was an officer in the

44th foot), I am happy to be able to pay this tribute to

American valor and American humanity; doubtless many mistakes

were made, errors of judgment prevailed in disregarding the

warning that the Capital might be attacked, but the charges of

cowardice against the American army will not be successfully

maintained by any historian who dispassionately reviews all

occurrences leading up to that fatal August 24, 1814, and who

has a due regard for American honor.

Miss Elizabeth Johnston said that the

massacre of the Susquehannock Indians is referred to as

occurring in the neighborhood of Piscataway Creek. The chief of

the Piscataways was, as the essayist noted, spoken of as ''the

emperor.''

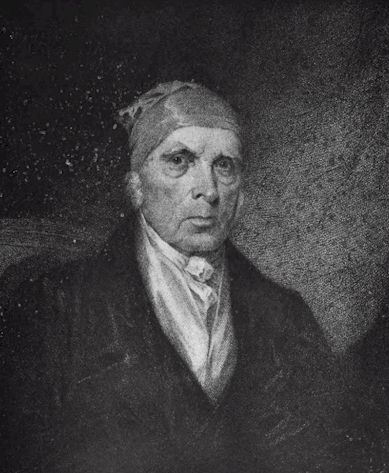

James Madison

General B. K. Roberts, commanding the

defenses of the Potomac with headquarters at Fort Washington,

said that with the present armament of the fort it would be an

easy matter to sweep the Potomac for miles downstream. Owing, he

said, to the elevation of Fort Washington, as well as the

batteries on the Virginia side, above water level, the force at

this point in the event a hostile fleet came up stream, would be

able to pour in a raking fire on the decks of the enemy's ship,

which constitute the weakest portion of modem war ships.

Footnotes:

1.

Marlborough Point was on Potomac Creek; and here as early as

1828, the steamer from Washington made connections with the

stage for southern and southwestern travel: "Time between

Washington and Richmond is 20 hour a, being 24 hours sooner than

by any other route.

2. McSherry's

"History of Maryland.

3. Bozman's "History of Maryland," vol. 2, p.

291.

4. 12th of May, 1704, Henry Knox, who was

Secretary of War under President Washington received a letter

which reads thus: The President of the United States who is well

acquainted with the river Potomac conceived that a certain bluff

of land on the Maryland side, near Mr. Digges', a point formed

by an eastern branch of the Potomac would be a proper situation

for the fortification about to be erected." The amount to be

expended for the fort was only to be $3,000.

5. "The troops stationed near Fort Washington

(Warburton)." National Intelligencer, July 20, 1813.

6. Social Life in the Early Republic," Wharton.

7. Original of Exhibits 1, 3 and 4 in Department

of State, Washington, D. C.

8. The British passed the kettle bottoms on the

ascent of the Potomac August 19 and reached Alexandria August

27. The kettle bottoms of the Potomac River are bars of mud and

oysters more frequently found between Lower Cedar Point and Cob

Point Lighthouse, a distance of about six miles.

9. Richard Wainwright, U. S. N.

AHGP

District of Columbia

Source: Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington

DC, Committee on Publication and the Recording Secretary, Volume

7, Washington, Published b the Society, 1904.

|

![]()

![]()